I’m back with a new queer author interview. Today we’re talking to my friend, Faythe Levine, the author of As Ever, Miriam. Faythe is an amazing writer, filmmaker, and artist and one of my favorite people to talk to about literally everything. Her new book revisits the letters between Charlotte Russell Partridge (1882-1975) and Miriam Frink (1892-1978), two women who lived and worked together in Milwaukee, Wisconsin for over 50 years. If that sounds gay to you, it probably was.

Quick backstory: Miriam and Charlotte met in 1915, while teaching at Downer College in Milwaukee. In 1920, they co-founded their own art school and a year later, in 1921, they rented an apartment together. Over the course of their 50+ years together, Charlotte and Miriam travelled extensively, raised dogs, designed and built their own house on Lake Michigan, and wrote thousands and thousands of letters back and forth. Their college, the Layton School of Art, emphasized interdisciplinary learning and strove to place both male and female students in stable, creative jobs. While Miriam’s side of the correspondence can be read and studied today at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee archives, only a handful of Charlotte’s letters to Miriam survive. And although Miriam’s letters are filled with expressions of love towards Charlotte and descriptions their life and home together, there are no explicit acknowledgments of queerness or a wider lesbian community. As Ever, Miriam plays with this erasure, and I was really excited to talk to Faythe about the difficulties and joys of looking for queerness in the past, making money as an artist, and strategies for sustaining a creative practice without burning out.

Maddy: How did you first encounter Miriam and Charlotte? Was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to create a book from their correspondence or was it a slow burn?

Faythe: Long answer: In 2001, I moved to Milwaukee, WI, after visiting a pen pal of many years who had moved there from Chicago. I lived in Minneapolis and was instantly enamored by the gritty industrial frozen-in-time still very cheap rent available. I moved there solo, and somehow, 15 years passed, with one stint of living in New Orleans, pre-Katrina, for 6 months. All to say, Miriam and Charlotte are very Milwaukee. I had heard about the Layton School of Art over the years before I realized it was founded and co-directed for most of its existence by two women. I thought I was leaving Milwaukee for good in 2015, and at that time, their full names and massive contributions to the city didn’t click. I moved back to Wisconsin in 2017, this time to Sheboygan (an hour north of Milwaukee on the lake) for a museum job at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

One of my first assignments as assistant curator was doing local historical research to weave into a fabricated history for an artist named Iris Haussler we were working with. I ended up working with their papers in the archive based on a memory of their story. It was kismet because once I was there, I had so many questions I needed answers to (this is always how my work starts). I was miffed that there wasn’t more scholarship around these two women who shaped the cultural landscape of Milwaukee. At first, I intended to write a combined historical biography. After a few years, it became apparent that because of the reach of their impact, this was beyond my scope without funding, and I knew I needed to narrow down my interest. I was also low-key obsessed with trying to connect them to a larger lesbian network or community (spoiler alert: I didn’t in the way I had initially wanted) and felt like their correspondence may be the key to unlocking that hope and was spending a lot of time with the thousands of letters between family, friends, and colleagues. It was here I began thinking about how one says goodbye; in Miriam and Charlotte’s case, over the course of a 50-year professional and personal relationship. So, I just leaned into that as my container to work within. Getting to that point took about three years, so the short answer is: slow burn.

Maddy: While reading Miriam’s sign-offs and goodbyes, I felt this sadness for her and had to keep reminding myself that Charlotte did write her back—it’s just that for whatever reason, her side of the correspondence never made it into the archive. I had to keep reminding myself that queerness resists categorization and even if there’s no explicit lesbian content, these two were committed domestic partners for over 50 years. What are the challenges of looking for queerness in the archives and did you, like me, also find yourself projecting your own agenda onto Miriam and Charlotte’s relationship?

Faythe: The idea of “queerness resisting categorization” is at the foundation of this body of work and something I wholeheartedly believe, so thank you for that framework of this question. Because of this, I’ve sidestepped from off-handedly referring to Charlotte and Miriam as lesbians, but I was 10000% drawn to their story because it oozes deep lez vibes, an IYKYK type of thing. This, along with my initial surprise about the lack of scholarship around their work was my motivation to dig deeper. During my research, I leaned into the fact that their papers were donated directly, meaning they decided what went into the Wisconsin Historical Society archive. So, I was speculating only based on what they chose to leave behind. Charlotte donated her papers while she was still alive (so I can conclude that she had Miriam's consent to include her letters). Miriam, who died two years later in 1977, requested that her niece, who had her papers because they had been working on a never-finished and unpublished manuscript of the Layton School of Art, discard certain items. There is no record of what was to be discarded; it was just that a request was made and noted in the collection finding aid. From this, I’ve deduced that Charlotte’s letters were a part of what was presumably destroyed or at best, saved by a family member.

I do have some theories rooted in queer speculation about why the letters aren’t included, but there’s no proof, and I’m okay with never knowing. But it was a surprise and a huge disappointment to discover the correspondence was predominantly one-sided aside from a handful (under a dozen) of letters Charlotte wrote to Miriam and a few small notes. From these and many other letters to family members and work colleagues, I know Charlottes' cursive script is barely transcribable. Still, from the few letters to Miriam from Charlotte that survived in the archive, I’ve gleaned that Charlotte, similar to Miriam, predominantly discusses travel and work updates and can confirm they are laced with a similar sentimentality to Miriam’s. I can go on and on, but I’ll wrap up with a specific personal challenge of looking for queerness in this work, which was remembering I don’t have to prove anything because this was not an academic paper where I had to show evidence. I did this work out of my interest in learning more about their both extraordinary and out-of-the-ordinary relationship and accomplishments.

Maddy: I think if you’re doing it right, every trip to the archive is a reminder of everything that’s not there. Miriam and Charlotte had access to education and economic opportunity, which meant they didn’t have to marry men in order to fulfill their basic needs. It makes me think about all the lesbians and queer women who were poor and not white, and how their letters and personal archives are lost to time. Can you talk about how erasure informs your work?

Faythe: All this is so true; their privilege is in the evidence they left behind. The way this question is showing up for me in this context is thinking about how I’ve always been a question-asker, sometimes to a fault. Where that has led me creatively is doing research-based work that I’ve often described as “filling in the blanks.” This is not usually to determine a final answer for something but to add to the conversation, to get people to ask more questions, and hopefully to generate more dialog or interest in something that there wasn’t attention given to previously. Unlike some people who can stick within a genre, my projects tend to jump around with my wide range of interests, so this has shown up for me in two major book and film projects: Handmade Nation: The Rise of DIY, Art, Craft, and Design (2009) and Sign Painters (2013). Both of these were fueled by motivation based on information I couldn’t find that I was interested in and felt would be valuable to share with a larger audience, as well as a fear that particular histories would slip by misrepresented or not documented. A much smaller representation of this type of project for me was working on the publication Bar Dykes (2015), a one-act play that had never been published, written in the 1980s about dyke bar culture in the 50s by my friend Merril Mushroom, who was born in 1941. I like to think my work is done with more mindfulness and care as I grow older; when moving into new spaces of inquiry, I don’t feel entitled to know everything based on my white cis identity. But I feel like, as an artist, it is my responsibility to share stories that can build pathways to understanding and feelings of connection with our past and potential futures.

As Ever, Miriam is rooted in all these motivations I named, but it was enjoyable to make it a bit more conceptual with how I decided to work with the material. By focusing specifically on their letters, the book highlights their intimately intertwined relationship and the craft of letter writing. Snail mail is something I feel very passionate about and was and still is foundational in my radical and queer networks. On the theme of white privilege, erasure, and archives, I want to name for those who may not be familiar with Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals by Saidiya Hartman. This book radically shifted and cracked open a space for my brain to think about archives, history, what isn’t told, and how it can be. I can’t recommend it enough.

Maddy: Tell me about your publisher, OK Stamp Press. I know they have a really different approach to publishing and selling books.

Faythe: Totally, they are such an important part of this book and how it lives in the world. M, who is the co-director of OK Stamp Press and designer of As Ever, Miriam, and I met as artists-in-residence in 2015 at ACRE, where I was finishing editing Bar Dykes. I knew from the socials she had joined maya, OK Stamp Press founder, and had been interested in their radical anti-capitalistic mutual aid model. What this means in their own words is, “OK Stamp Press operates on the principle that books are communal culture and build relationships. These vary and include relationships between authors and readers, ideas and readers, readers and publishers, ideas and community. We, therefore, disseminate all our book projects according to a mutual aid principle: reader funds should circulate within reader communities.”

This means that if someone wants to buy a book from them online, the buyer donates the book's list price, listed on the publishers' website, to an organization. For my book, I give two suggestions of places to donate. Cactus+ is based in Milwaukee, where Charlotte and Miriam worked and lived, and Kite’s Nest is near where I live in the Hudson Valley. Then, the buyer emails documentation of that donation to the press, and in turn, they send a book. So, there’s no monetary exchange between the consumer and the press; all money goes back into the community. It’s all outlined clearly on the website. As Ever, Miriam, like all of their books, was printed as a small edition and is available online through the press, at a few independent booksellers, or through me directly. I hope to recoup some of my expenses by direct sales, but it’s a labor of love from all directions. I’ve worked with larger publishers and never made much money (in relation to the cost of making the work) from my book sales, so this feels more aligned with my politics. If there ends up being a second pressing, I’m not sure what that will look like yet.

Aside from how the press operates, there’s a lot to unpack here. For example, I have a day job that supports me, and I’m not currently relying on my creative practice to make a living. But I’d like to recoup some of my expenses from working on this for over 5 years, and this will likely happen by doing programming where I am a visiting speaker, guest artist, or in a paid advisory role of some sort. Historically, I’ve made the most income from this type of institutional support, not from direct sales of my work. As you may glean from my long-winded answers, I enjoy talking about what I’m doing, with the hope that sharing my less traditional ways of doing things can help others break out of feeling like they need to follow a more typical path previously laid out.

Maddy: Thank you for talking about the financial realities of book publishing. I think a lot of people assume that authors can make a living from writing and publishing books, when in reality that’s super rare.

Faythe: It’s so important to weave conversations about money, privilege, and class into our creative discourse. Part of that work, for me, is my investment in demystifying what it means to be a “working artist” or “successful” because there is so much that no one talks about and the definitions can mean such a wide spectrum for different folks. For example, if you don’t come from generational wealth or have a partner who can support you, there’s no framework for understanding how people do it, we just see images of success on social media and feel like we are falling short, or at least I do that. My experience has been rooted in what many people would consider financially irresponsible behavior that involved taking a lot of risks that I wouldn’t recommend for everyone. They are definitely not risks I would take in my 40s, but in my 20s, they seem reasonable as an able-bodied person with no kids or other family obligations. Maybe it’s becoming less taboo to discuss credit card debt, second or third jobs, or family support, all three of which were major players at different points in my career path, but it still seems clunky and laden with all sorts of shame (both from people who have money and who don’t). Anyhow, it’s an integral part of talking about my work, especially with students, because I’ve made a lot of missteps and had a lot of what we call success, but not by making traditional “smart” decisions. There’s just more than one way to get something done, is part of what I’m saying.

Maddy: My last question for you is a BIG one: you’ve been an artist, writer, and all-around creative person for most of your life, and I’m wondering what keeps you going. Do you have any advice for building a sustainable, joyful creative practice?

Faythe: Ha, well, get ready for my last BIG answer! I’ll start by saying I’d describe my former self as a work addict. For more context, I’m turning 47 this month (for you astrology gays, my Sun is in Scorpio, Moon in Aries, and I have Sagittarius rising with an exact Venus-Uranus conjunction in Scorpio). Saying I’m 47 feels bizarre to write, not because I’m bummed about getting older, but because I feel the same pressing, “I have so many ideas, how will I ever get them done” feeling I had when I was 25, but my energy level/attention span/memory recall is significantly less than it was even 5 years ago. This shift is in alignment with lots of mind-melting variables and feels like a cocktail of latent pandemic vibes, my own ongoing chronic health issues (shout out to those of you living with endometriosis, any other invisible disease or disability), and peri-menopause.

I’ve done a lot of intentional work for years to push back on the curse capitalism put on me (and all of us) for feeling guilt around resting and not getting enough done. I still struggle with my inner critic on the daily who tells me I could have done more, done better, or done something faster… but I now have the tools to quiet that nagging voice to take care of myself. Unfortunately, It took me having intense burnout in 2015, paired with a major breakup that spiraled me into a black hole that took a few years to climb out of. I’m proud of how far I’ve come from that unsustainable manic work style, and I no longer think burning the candle from both ends is a good idea or cute. If you are in the depths of significant change, I’ve seen the other side, and my advice is to take it one day at a time, ask for help, and be gentle with yourself.

My biggest tool for sustainability is my calendar. It’s my tool to think about macro and micro scheduling for mental health, project timelines, and planning. I also need a calendar deadline to finish something, and my deadlines are more often than not self-imposed. This is why I recently started a Substack, a place to dump thoughts and ideas that were backing up in my brain. It’s not a technical deadline but a space that motivates me to get some things out. But this can also look like collaborating with someone or setting a date for an opening or event, so then there is accountability for finishing something. I have a long history of talking about a project online and generating interest, then needing to finish the project because there is an expectation—nothing like self-imposed social pressure to get shit done.

Sharing things I’m excited about brings me joy, and that’s at the foundation of what I do creatively. How it’s manifested has shifted over the years, but I will always love the materiality of a book/zine as a format of sharing. A close runner-up is putting together an exhibition. Sometimes, my creative work has been my day job. Sometimes, I’ve worked a full-time job and made work on the side. I’ve intentionally stopped saying it has anything to do with luck; for context, I initially wrote that sentence, “I’m lucky. Sometimes my day job is also my creative work,” I’ve worked my ass off to make all the different things I’ve done come to fruition.

Thinking about authentic motivation and why you are driven to create is essential; trusting your gut and feeling excited can be the best motivation. If possible, set aside anything to do with paychecks, social media, and social capital. I also encourage people to think about their time as an investment. Separating money from creative practice is a privilege, so separating them may not be possible. Figure out what works for you and create systems to work within, knowing they can shift and change over time. We all need to lean into our communities and form authentic connections as the world around us continues to crumble. Shit is heavy, and it’s our responsibility to continue to push back, and being connected is an active part of that resistance. Maddy, you do this so incredibly, and I deeply appreciate this space to think about these thoughtful questions. Thank you for folding me in and all you do for us!

Gift subscriptions to TV Dinner are 33% off until the end of November. You want it and so do all your friends.

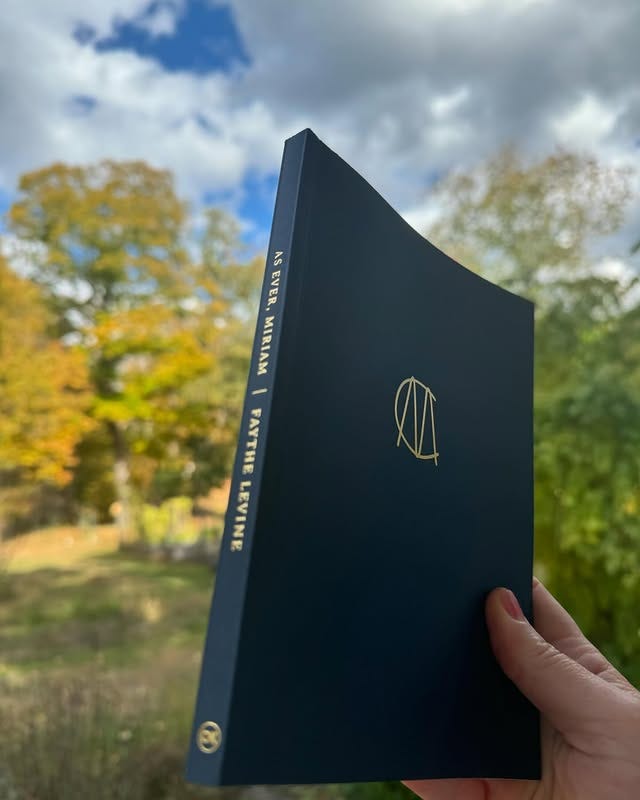

As Ever, Miriam is available now from OK Press or from the author directly. Not to be shallow, but I have held this book in my hands and it is beautiful and includes a pull-out timeline of Miriam and Charlotte’s lives. It would make a perfect holiday gift for you or your friend who loves The Lesbian Herstory Archives, the city of Milwaukee, and the Wikipedia article, “Boston marriage.” You can learn more about Faythe and her multifarious projects on her website. I highly recommend her newsletter, The Thumb Tack, and you should subscribe immediately 👯🏻♀️

Loving Corrections with adrienne maree brown 💕

If you are a queer person who knows other queer people or someone who’s invested in social justice and community activism, you have 100% lived through a nuclear breakup, cancellation, and/or been called upon to never speak to someone again. Loving Corrections,

Thanks for having such a thoughtful conversation with me Maddy! Appreciate you <3

ahh ok, saidiya hartman/critical fabulation changed my life and any book that employs that method moves straight to the top of my top be read pile! thanks for this interview, can’t wait to read it.

related, i’m currently reading this book that is also lesbian love stories pieced together from the archive, mixed with memoir…https://bookshop.org/p/books/lesbian-love-story-amelia-possanza/18814965?ean=9781646221059

i love lesbians ugh we’re the best