Hello! I’m back with another queer author interview, this time with author Emma Copley Eisenberg. My goal for this series is to highlight gripping, next-level fiction and nonfiction and resolve the “I want to read something but I don’t know what“ conundrum that I’m constantly hearing from friends and T.V. Dinner readers alike. So this is me, telling you what to read. I hope you like it :) xoxo, Maddy

Housemates, a new novel by

, is a love story between Bernie, a working class photographer, and Leah, a writer who’s spinning their wheels in grad school. They meet when Bernie applies to live the house Leah shares with their girlfriend and a handful of social justice-oriented queers in West Philly. From opposite sides of a thin bedroom wall, Leah and Bernie overhear each other cry, have sex, and otherwise live out their daily lives. Sensing that Bernie might be the answer to all their questions, Leah convinces her to collaborate on an art project that will change each of their lives forever. Set in 2018 during the Trump administration, Housemates is also a reflection on America and what it means to find hope in a country that’s marred by violence, capitalism, and gross inequality.Emma and I went in on a Google Doc about the historical dykes who inspired Bernie and Leah. We talked a lot about writing, specifically how to get over writer’s block and write about bodies in a world that refuses to be normal about fat people. I learned so much from Emma and hope this interview inspires you to get a copy of Housemates today.

Maddy: Housemates is about a road trip and young artists trying to figure out what kind of art they want to make, and it’s also a queer love story nested within another queer love story. There’s so much about inheritance and generational differences and many other big, systemic themes like economic inequality and fatphobia. I loved Housemates but when my girlfriend asked me what it was about, I had a hard time summarizing it for her. How do you describe this novel?

Emma: Touché, your girlfriend! I have at times been accused of being a maximalist, of throwing everything I care about into the book I’m writing. But I would say that Housemates is a book about the question, “can art save your life?” In terms of plot, it’s about a chaotic queer group house in Philadelphia in 2018 where two of the housemates, Bernie and Leah, both want to make good art but can’t figure out how. Bernie has a vaguely creepy former photography professor who dies in central Pennsylvania and leaves her his photographic estate and Leah invites herself along for the ride because she’s desperate to get out of digital journalism and academia. As it turns out, they need each other, and the road trip they end up on, to find the answers to lots of questions they have about work and class and fatness and hot sex and how to be a “good queer,” and America.

M: Bernie and Leah’s story is narrated by an older lesbian, Ann, who spots them in a coffee shop one day (West Philly stans will clock Satellite Cafe). While I was reading Housemates, I wondered if Bernie and Leah’s road trip romance was a fantasy of Ann’s or even fanfiction based on their photography project. Ann, as I read her, is closeted and seriously disconnected from her own emotional world, and she feels a certain fascination with all the young queer and trans people she sees in her neighborhood of West Philly. Why did you structure the book this way and what interests you about generational differences re: queer lives and relationships?

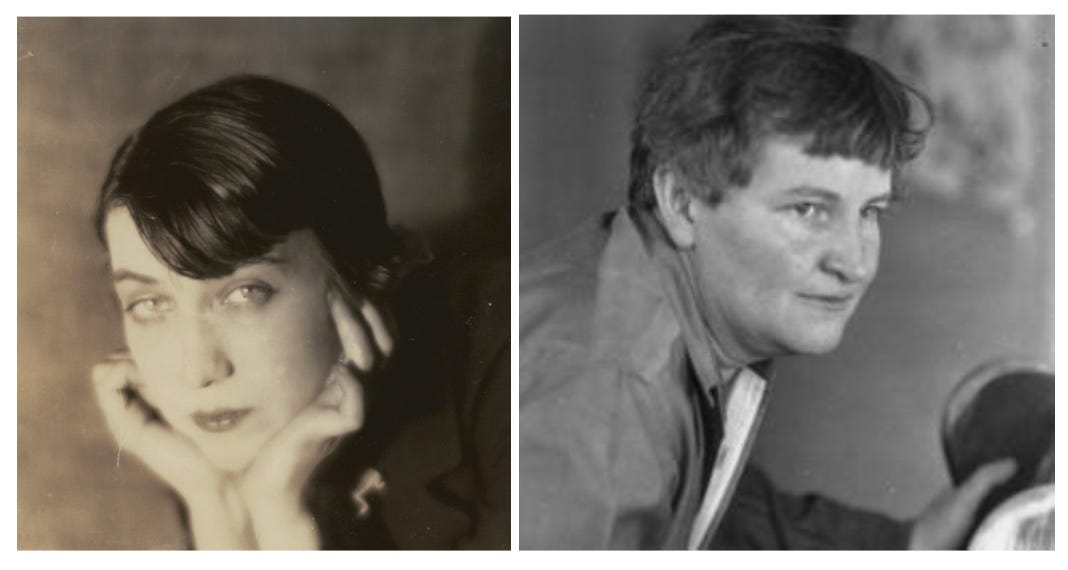

E: I love these interpretations (fantasy, fanfiction) and all of them are very welcome and astute! So the simplest answer is that this novel began from an interest in two real historical queers Berenice Abbott, an influential modernist large format photographer who photo nerds have maybe heard of, and her creative and romantic partner, the art critic and socialist Elizabeth McCausland, who almost no one has heard of. (Only sort of relevant, but they were both certifiable babes.)

By chance I saw a show of Abbott’s and then read this great biography and learned that Abbott and McCausland went on a road trip together throughout the southeast United States in 1935. They both left for the trip single and creatively adrift, not sure what they wanted to do with their lives or what kind of art they wanted to make, and they came back together (U-Hauled into an apartment in NYC) and with great clarity that they wanted to do a project together to document America in words and photographs before it changed dramatically during the Great Depression. I became obsessed with knowing what might have happened on that road trip that changed everything, and in thinking about how two queer women artists can figure out how to be both separate and in a partnership.

I didn’t want to write a historical novel, not least because a good one about them has already been written but also because I am really obsessed with the now, what it means to be a queer person artist trying to love other queer people today, and I wanted to set the book in 2018, right smack dab in the middle of Trump’s presidency and before things changed again in ways we didn’t yet understand. But I did want to find a way to widen the novel, to direct the reader’s attention to the question I cared most about in writing, which was “can art save your life?” That’s where Ann Baxter came in. I wanted the book to be told from the POV of someone who shared Bernie and Leah’s neighborhood, and, to some extent, Bernie and Leah’s story, but was of an older generation and for whom the stakes of that question were much higher. I had a lot of fun writing from an older POV and playing with all the ways it is both easier and harder now to be a queer woman artist than it was in decades past.

M: It strikes me that Leah is a writer who doesn’t know what to write, while Bernie and Ann are both photographers who have stopped taking photos. I’m wondering if there’s something distinct about how queer women artists become blocked and disconnected from their own creativity? Bernie is tired and burnt-out from working multiple jobs, but it seems more existential for Ann and Leah.

E: Damn, I hadn’t thought about this before but I think yes? Leah is nonbinary but yes, I do think there is some element of blockage at play for all three of them that does have to do with their identities, though they each also have their own reasons—Bernie is grappling with the sense that her eye has been somehow tainted by her dead photography professor who crossed sexual boundaries with her peers, and Ann is grieving her dead life partner. But for Leah the reasons are more of the “how should a person be?” variety, which maybe is typical of writers, hehe. Leah knows all the things she doesn’t want to be but none of the things she does, she finds fault with every way of being, every possible subject, often from a moral or ethical standpoint. Leah is very of the neighborhood where the book takes place, West Philly and Swarthmore College before that, places that are deeply invested in what it means to be the “right” kind of queer — politically active, intersectional, oriented towards the collective. In many ways, Leah is ambitious, selfish, and snobbish, but is afraid to be these things or to move in any direction that could be considered wrong, hurtful, or privileged. Yet making art requires vulnerability and making moves, staking your flag somewhere. There may be a particular investment in pleasing people and in being moral that can plague and stagnate AFAB queers.

M: While we’re on the topic of artists not making art, do you have any tips for overcoming writer’s block or other kinds of creative dry spells? Does it require a road trip? Asking for a friend (me).

E: Why yes, yes I do. I really like Alex Chee’s essay on the subject in which he says, to my mind, that writers block isn’t like a complicated existential mystery, it’s basically just shame, shame that you aren't writing and then the shame of not having written compounds, growing ever bigger the longer you don’t write. This is basically true for me, so usually I just have to realize that and then realize that the sooner I deal with the shame the sooner I can get back to writing. But also I’ll add something from the writer Ron Carlson, whose book Ron Carlson Writes a Story is basically the only craft book about writing fiction I like (buy it used because, like Daniel Dunn in Housemates, RC is a creep). Carlson says “the writer is the person who stays in the room” and, I’m paraphrasing, the thing that kills us is writing a sentence or two and then getting up and leaving the room, because when we do that there is some magic sensing intuition that was birthed in the writing of that sentence that we’ll never get back. I think, unfortunately, that this is true. I believe in ass in the chair logistics, in saying you will write for even 30 minutes and staying for the full 30 minutes. I believe that all writers feel like frauds because they’re sitting there in the room and they don’t know what they’re doing but that the main artistic difference between a creatively “blocked” person and Maggie Nelson or Terrance Hayes or [insert your idol here] is that they encounter that feeling of “I don’t know what I’m doing” and they stay there in the room anyway. They don’t leave. Whenever I force myself—through cheap artist’s residency done at an Airbnb with friends or a schedule my partner will judge me for not keeping—to stay are the times when I’ve done my best work. Road trips are not usually writing generative for me, but they sure are fun, and they are often huge relationship closeness accelerators.

M: I loved the sex scenes in Housemates, and also the way you describe Leah and Bernie’s bodies throughout the novel. I was really struck by this moment where you describe the way Bernie walks as a very thin person, specifically the way her ass appears and disappears as she extends her legs. There’s an undeniable freakiness to an ass disappearing and reappearing like that but in literature, detailed descriptions about how someone moves, especially the way they walk, are usually reserved for fat characters. Is there a connection between how you approach writing about movement, sex, and bodies? Like, how are you SO GOOD at it?

E: Hehe. Everybody moves, everybody’s body is part of the plot. In fancy grad school for creative writing, I was taught not to give the body, to give only a unique mole or line of a collar bone, because giving the body was for cheap genre writers, like romance and mystery. Well so be it then, maybe I am a cheap genre writer in the sense that my genre of choice is human beings and how they really are, how it really feels to exist within this strange skin suit and look out through these eyes at other people in their skin suits. People’s bodies profoundly shape how the world treats them and how they treat the world. My goal with writing the character of Leah was, among other things, to write a fat character whose body was not a problem to be solved – Leah is fat and ambitious and neurotic and Jewish and she doesn’t lose weight by the end of the novel nor does she come to “accept” her fatness in a way that means she no longer struggles with living in a larger body in a deeply fatphobic world.

But Bernie too struggles with her body, even though she is thin – she is really dissociated from her body, says early on that she “forgets” about her vagina and that it has “no voice.” She is struggling to be present in sex and have sex that is actually satisfying. So the moment I knew Bernie and Leah were attracted to each other, I knew that when they had sex it was going to be a really big deal and that the book was going to have to linger over the sex scenes for a long time because both characters were going to be transformed by it. That’s the key to writing good sex I think – pay attention. What is getting revealed in this scene that only physical intimacy can reveal? Leah is powerful in sex and Bernie is not in a fun reversal that means everything in their relationship. That and – don’t half close the door on the sex scene. A lot of writers do this, sort of squinting at the sex scene with their lids half closed. It’s still a scene. Every action matters. Every placement of every hand and how it feels matters. That’s how I experience sex anyway – the placement of everyone’s hands is what I remember.

M: Oh wow, I think about hands too. Thank you so much for the solid writing and body-having advice, Emma.

E: The delight has been all mine! Anywhere there is advice about what to do in messy queer love affairs is a place I want to be.

Housemates is available from your local library, indie bookstore, or haunted Barnes & Noble that, along with a Kohl’s and Spirit Halloween, is the only remaining business keeping your childhood mall afloat. This is a novel that will resonate with anyone who processes their big, queer feelings with a long walk or drive, artists who don’t know what to make next, and anyone bored with fatphobic literature. You can read the first chapter here. Emma also writes Frump Feelings, a not-to-be-missed newsletter about “writing, books, ice cream, and fat liberation” that you should subscribe to as soon as possible. 🏠

How it Works Out with Myriam Lacroix 💄

I’m really excited to bring you a new queer author interview. This time around I’m talking to Myriam Lacroix, the author of How It Works Out. This book is divided into 8 stories—each story takes two lesbians, Myriam and Allison, and imagines them and their relationship anew. In “Anthropocene,” Myriam is a wealthy CEO with a humiliation kink and Allison …

Life goal unlocked! xx

This is the best book I read this summer! I hope your interview inspires more people to pick it up :)