Hello! I’m back with another queer author interview, this time with poet Tiana Clark. My goal for this series is to highlight gripping new books and resolve the “I want to read something but I don’t know what“ conundrum that I’m constantly hearing from friends and T.V. Dinner readers alike. This is me, telling you what to read. I hope you like it :) xoxo, Maddy

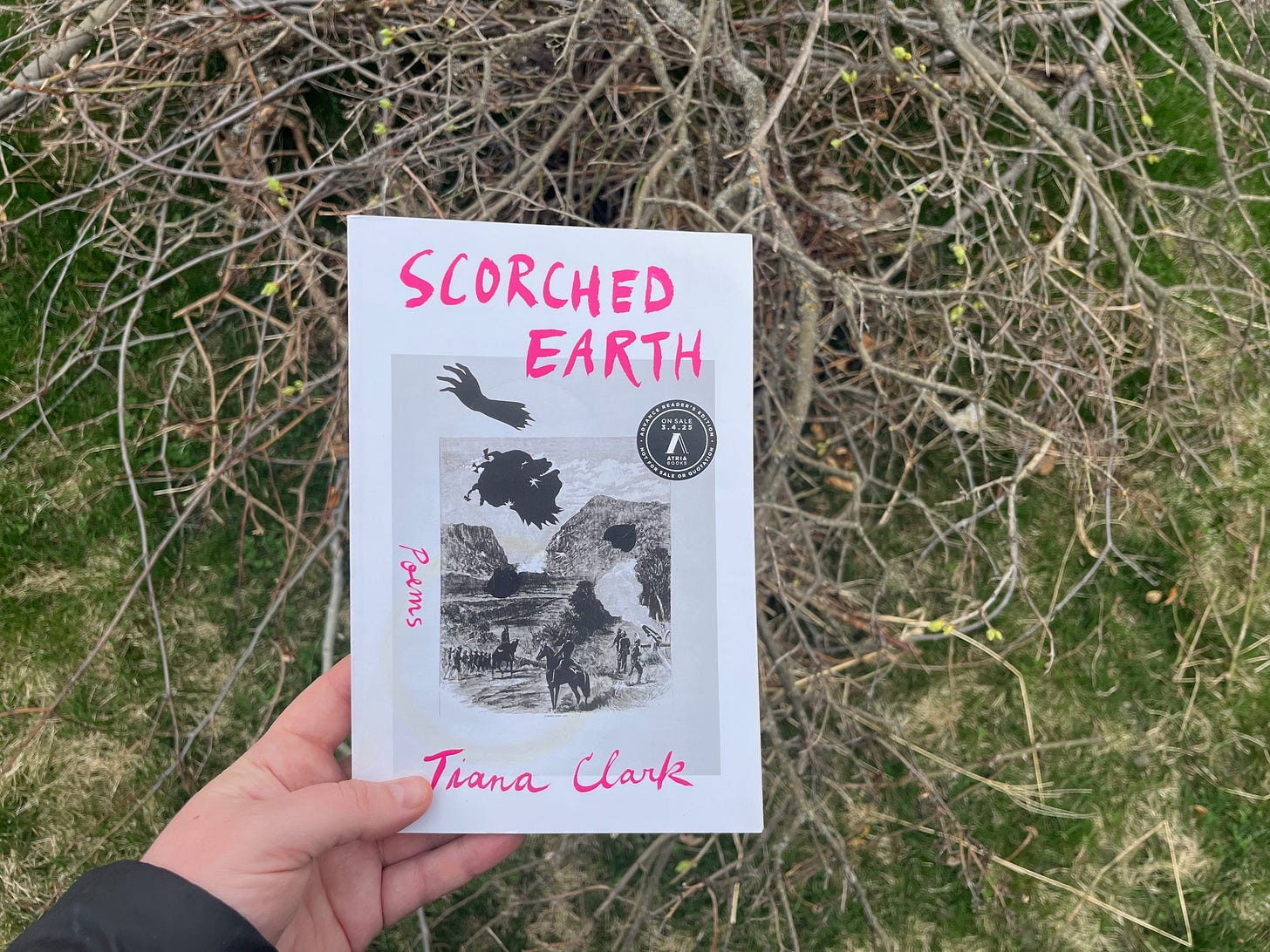

Scorched Earth, a new collection of poetry by Tiana Clark, explores the queer possibilities and personal upheavals that arise after the speaker’s divorce. Quick confession that I don’t read enough poetry and I needed this reminder that poems are cool as hell. They can move sideways and get into cracks of the human experience in a way that prose cannot. The poems in Scorched Earth, for instance, cover so much ground: motherhood, multi-racial identity, the innermost thoughts of the first Black Bachelorette, and Cardi B’s teeth. I loved how funny and deeply-felt this collection is, like reading a text from a friend who’s trying to process a big, complicated breakup or self-realization, but not taking herself too seriously in the process. I especially appreciated how horny many of these poems are e.g. this line in “Proof:“ “I want to touch you / like a mirror touches, / everywhere at once.”

In honor of Scorched Earth’s release, Tiana and I met up in a shared GoogleDoc to discuss the role of poetry in a backsliding democracy, Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic,” and why it’s vital to write about Black pleasure and love. I left this conversation with a lengthy list of books, movies, and songs to track down. Tiana is a total visionary, and I hope this author interview inspires you to track down a copy of Scorched Earth today.

Maddy: Your poems “My Therapist Wants to Know about My Relationship to Work” and “After the Reading” describe the strange and difficult labor of being a poet who shares their work with the world. Why do you write poems and how do you keep showing up for your own work when everything feels impossible?

Tiana: Oof! What a thick and amazing question, Maddy. I’ve been wrestling with the latter half of your inquiry–especially now, when everything streaming from the news feels like a constant horror show. One way I keep showing up to the world and my work is leaning on poets that I deeply admire. Lately, I’ve been thinking about the last three lines from Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem, “The Second Sermon on the Warpland,” which says:

It is lonesome, yes. For we are the last of the loud.

Nevertheless, live.

Conduct your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.

What does it mean to “conduct your blooming” in the chaos of this current political hellscape? I am trying to figure that out as I try to honor whatever is flourishing within me.

There’s an incredible story about Nina Simone when she found out about the racist assassination of Medgar Evers in 1963. She was, of course, grief-stricken and furious as she tried to find a gun in her house because she felt like she had to do something. Since she couldn’t find a gun, her husband at the time found her in a frantic state and led her to the piano where her thunderous rage spilled through her shaking fingers as she wrote and sang her first Civil Rights song, “Mississippi Goddam.”

This potent example shows me how to make my anger useful—how to alchemize my anger into action, art, and protest. I believe language fails us as much as it saves us. With all the violent erasure of Black and Trans people right now, I feel that art that gives us back our humanity is vital. Reading and writing poems makes me feel possible–even against all the impossibility. A poem can’t save my life, but it makes living more bearable.

M: Sex is a big force in Scorched Earth and queer sex looms especially large as a homecoming, as well as a new era in the speaker’s life. I don’t have a specific question because I don’t want to seem nosy, but can you say more about this?

T: Ha! Yes, more PLEASURE, please! Especially at the end of the world! I appreciate the spirit of this question that no one has asked me yet! So, thank you!

My first book had a lot of pain—Black pain—which was important for me to explore and examine the brutality in the historical archive. But in that quest, I think I forgot about the importance of beauty. I think I forgot about the Black body experiencing desire. It’s important to me that when I talk about Black lives, it’s not only about suffering. Suffering cannot be the only lens to access the holistic breadth of Black life.

Though, I want to make a vital distinction here: it’s crucial for us to remember, to look back, and not only confront the horrors of American history, but also to name them completely and forever. Particularly now, with this corrupt administration, which is actively and violently erasing and threatening so many vulnerable lives already at the margins of our society. I want to make sure that’s undeniably clear.

However, if the main narrative is only about Black pain and struggle, then what does that important, but also narrow, perspective communicate about the multifaceted nature of Black humanity through literature and mass media? I want to survive, but it can’t just be about pure survival only. What comes after survival? I want to deeply know what it’s like to thrive as well.

The first roles that Black actors were allowed to play were flawed and negative stereotypes conjured from the racist imagination. Think: Hattie McDaniel’s “Mammy” character in Gone with the Wind. Seeing the Black Panther movie was fun and impactful to watch, but I don’t want our flourishing to reside only in the realm of science fiction—in a fake kingdom that doesn’t even exist. Heck, even in that make-believe world of Marvel, Wakanda still had to be invisible and hidden. It couldn't truly exist without the threat of annihilation. I want to keep creating and reflecting back Black beauty and pleasure. I want more “Black abundance” now–borrowing Kiese Laymon’s incredible refrain from his memoir Heavy.

Of course, I’m not the only Black writer thinking about this, but there is a dearth. Though, I think The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw is a great example of a fantastic short story collection that captures the full lives of Black people experiencing pleasure and pain in equal measure. Highly recommend “Eula” as one the best Black, queer short stories I’ve ever read, colliding faith and sex in such a marvelous and brilliant way!

I crave more stories like “Eula,” portraying the nuances of pleasure in Black love, instead of what we usually see on our TV screens: dead or broken Black bodies, exploited as pejorative tropes. And when we finally get a show featuring a leading Black lady trying to change her life in wacky and wonderful ways, like Natasha Rothwell’s whip-smart comedy, How to Die Alone, it gets cancelled after one season on Hulu. Yes, I know we had Insecure, which was fabulous and groundbreaking. Don’t even get me started about the L Word: Gen Q reboot—phew! Though, I will say that I LIVED for your incredible recaps, which kept me laughing in the WTF-wake after each episode, ha! I know there are a handful of other shows to name, but the list does not match the surfeit of white-centered stories and characters in media. Why can’t I have more?

I wanted to lean into that moreness for Scorched Earth. More sex! More pleasure! More kissing and touching! More delight, and more of me, exploring my queerness through the speaker in my poems, which is a mélange of real and imagined scenarios. Though, I will admit that I write pretty close to the contours of my real life. I wanted a more realistic, honest, and self-aware book that revealed more than it concealed. I wanted to risk clarity in my queer longing. I was tired of hiding and being afraid, which is why my book begins with this epigraph from the stunning poet, Aracelis Girmay: “…I’ve been remembering the story of salt. Lot’s wife. / But you tell me something the story never did: / Look back at the burning city. Still, live.” I interpreted these lines as a powerful imperative that reimagines survival instead of a pillar of salt. In this reimagined version of the Bible story, there is no death from disobedience in the face of destruction, only a reminder that I can bear witness to any apocalypse. I can look and not be destroyed by my desires, desires that I waited too long to name.

Of course, I have to mention the salient essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” by Audre Lorde, who reminds me about the “replenishing and provocative force” of sensuality and joy-drenched reclamation “to risk sharing the erotic's electrical charge without having to look away…Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world….”

I will end my long answer here with these wise words from bell hooks about Toni Cade Bambara:

She wanted me to remember that pleasure is political–for the capacity to relax and play renews the spirit and makes it possible for us to come to the work of writing clearer, ready for the journey.

M: In Scorched Earth, you really capture the surrealness of divorce and the experience of looking back at a significant relationship and both recognizing and not recognizing that version of yourself. I know you write close to the bone, so how do you approach writing about people in your life and things that have actually happened to you?

T: If I write about someone in my life, then it’s important for me to interrogate myself just as much as I am interrogating someone else in my work. I often try to wait and marinate first before writing the poem in the hot heat of hate or bitterness. While I am processing, I still might write the messy ass poem for myself, but I will never publish that poem. I wait until time (and therapy, ha!) has softened me, until I can have a more balanced perspective on what happened. I pause until I can see beyond just my pain alone, and if it’s possible… until I can begin to see the humanity in the other person or people.

Although, I want to preface that I understand this kind of grace may not be accessible or even reasonable for some people to possess or process—which is totally valid! Don’t rush forgiveness, especially if it is not possible, available, or harmful to your healing. I echo Elizbeth Bishop’s sentiments here, writing to Robert Lowell, “Art isn’t worth that much.”

The first poem I wrote about my divorce was “Proof,” which is the prologue poem of the collection. My approach for this poem was self-implication—a key factor, I think, in writing about other people, especially in terms of heartbreak. Although I am divorced, I still made a vow to honor my ex-husband that I want to uphold as exes. I wasn’t interested in bloodletting the juiciest details of our discord. I wanted to challenge myself to write about my divorce without disrespect, which kept me (mostly) grounded throughout the process of writing through the mercurial waves of grief that would slap and knock me down during the healing.

In terms of the real vs. emotional truth… I think this is where the lyric “I” comes into play. The poetry first person POV, to me, is a collage of real and imagined experiences. A lot of people misconstrue poets as pure memoirists—and we are not. Or, at least, I should say, I am not. Yes, I write close to the bones of my real life. Yes, many of the details are technically true or mostly true enough. But it’s important for me to make that distinction as a way to create some psychic distance for myself and my readers. Poets can dip into the toolkits of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and all the liminal spaces in-between to create a tapestry of human connection through verse. We can weave and slip in and out of what did happen, what we wanted to have happened, and what we hope could possibly happen in the future. We can change names, dates, and view real people in our lives as characters in a novel to access the potent marrow inside our poems. Doing so, actually makes it easier, in my opinion, then sticking to the fact check of my real life.

This is all making me think of Emily Dickinson’s famous paradox: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant —" A real tickle pickle for the mind! For me, this line, and the whole poem, is about many things, one aspect being: the caution and care it takes in telling the truth. The real truth can be too bright at times, for others, and even for myself, to process and see at first like the lightning mentioned in the poem. This is why letting the real facts ferment in darkness is crucial for my poetic process in accessing the emotional truth. I want to pause and stretch that spark to electrify the whole poem as I wrestle with the truthiness.

M: In honor of National Poetry Month, what’s one book of poetry you would recommend for this moment?

T: American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes. This collection, written during the first two hundred days of the Trump presidency in 2016, employs the rhetorical squeeze of the sonnet form to reckon with American racism and political madness. Hayes says the sonnet is a form you can scream into, which was apt then and even more relevant now, since the terror has boomeranged back in 2025. These poems are playful, scathing, and bursting with vibrant sonics and innovation. I reread it recently with my class last November, and it was the exact book I needed to help me process my political rage, fear, and disillusionment. It’s striking to me that Hayes wrote this book while holding the space for the “future assassin,” which seems prescient to me now. 💥 🌎

Scorched Earth is available NOW from your favorite bookshop or library. This is a collection of poems for hot divorcées, queers who grew up in high-control religions, past and current residents of Nashville or Madison, WI, and/or bibliography freaks. You can learn more about Tiana and her poetry here.

American Bulk 🛒

It’s often said that we don’t own our possessions, our possessions own us, but I also feel owned by things I don’t possess yet and maybe never will. Ask me about my devotion to the Reddit page r/buyitforlife, for instance, or the profound guilt I feel returning online purchases, knowing they’ll just be bundled up and dumped in a landfill somewhere. When…